2020 Housing Bills: Legislation in an Age of Uncertainty

Updated July 28th, 2020 | Embarcadero Institute Board

1. Introduction

Amidst profound uncertainty caused by the Coronavirus pandemic and new economic climate, California’s State Senate and Assembly have pressed ahead with a flurry of housing bills that attempt to address the state’s housing challenge. A number of these bills represent adaptations of earlier upzoning bills, including the heavy-handed SB-50 which failed in a Senate floor vote in January 2020. Other bills pursue developer bonuses and incentives for moderate-income and market rate housing, with little obvious benefit to lower-income households. These bills also create new complexities and potentially set up conflicts between local land use and state law — with no clear path for resolution.

The Embarcadero Institute has prepared a summary analysis outlining each bill’s potential effects, benefits, interactions with existing legislation, and inconsistencies. The bills can be broadly categorized into six buckets, defined by their approach and potential impact. Some fall under multiple categories:

- Upzoning: Bills that increase the allowable density for housing projects in an area regardless of local zoning standards. These bills are designed to make higher density housing (including duplexes and multifamily units) a use “by right” in cities with controls on maximum density. Proposed bills that allow upzoning of parcels include AB-1279; SB-902; SB-1120; and SB-1385.In general, these upzoning bills are not as heavy-handed as the failed bills SB 50 and SB 827 which would have superseded most local zoning controls and allowed high density, multifamily development in many lower density neighborhoods.

- Streamlined Approvals: Bills that seek to reduce the time, cost, or other requirements (e.g. CEQA) to approve a housing project by a local government. Proposed bills include: AB-3155; SB-995; SB-1085; and SB-1120.

- Developer Incentives: Bills that provide incentives for housing developments in exchange for creating additional affordable units. Incentives can include density increases, reduced parking requirements, reduced design requirements, etc. Proposed bills include: AB-725; AB-1279; SB-1085; and SB-1385.

- Commercial Site Redevelopment Incentives: Bills that incentivize the redevelopment of commercial and/or office sites to provide housing, especially those that are vacant or underutilized. Proposed bills include SB-1299 and SB-1385.

- Funding: Bills that provide direct funding to state or local agencies to construct or support affordable housing. Of the proposed bills only SB-1299 has a major funding component.

- Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA): Bills that affect the regional housing needs allocation (RHNA) targets set by the Department of Housing and Community Development. AB-3040 affects the current allocation requirements and credit system. AB-725 and AB-3040 both change RHNA requirements.

2. Bill Analysis and Context

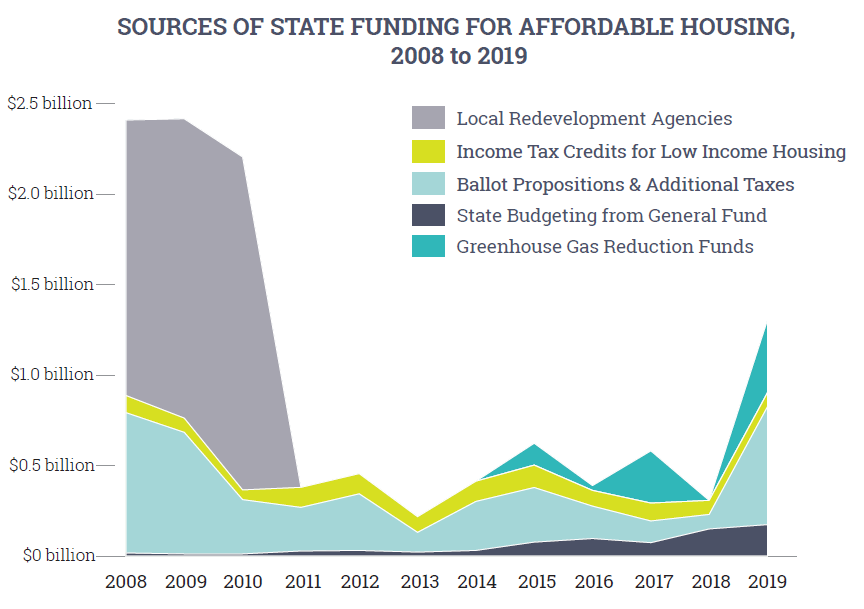

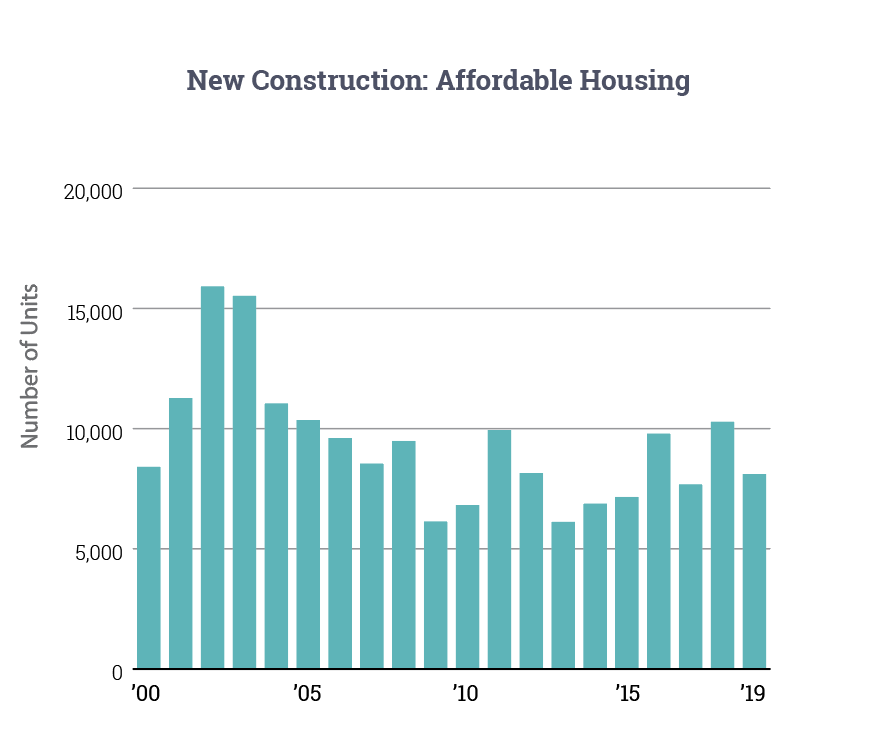

During the Great Recession, the state terminated most of its funding for affordable housing by shuttering local development agencies (RDAs) (see Embarcadero institute, 2020). At the time, RDAs were providing 80% of the state funding for affordable housing through the redeployment of local property taxes. Facing a budget deficit, Governor Brown froze local redevelopment activities in 2011, and shuttered the agencies in 2012, diverting their property tax resources to schools and local services to backfill the state funding shortfall (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Sharp Decline in State Funding for Affordable Housing

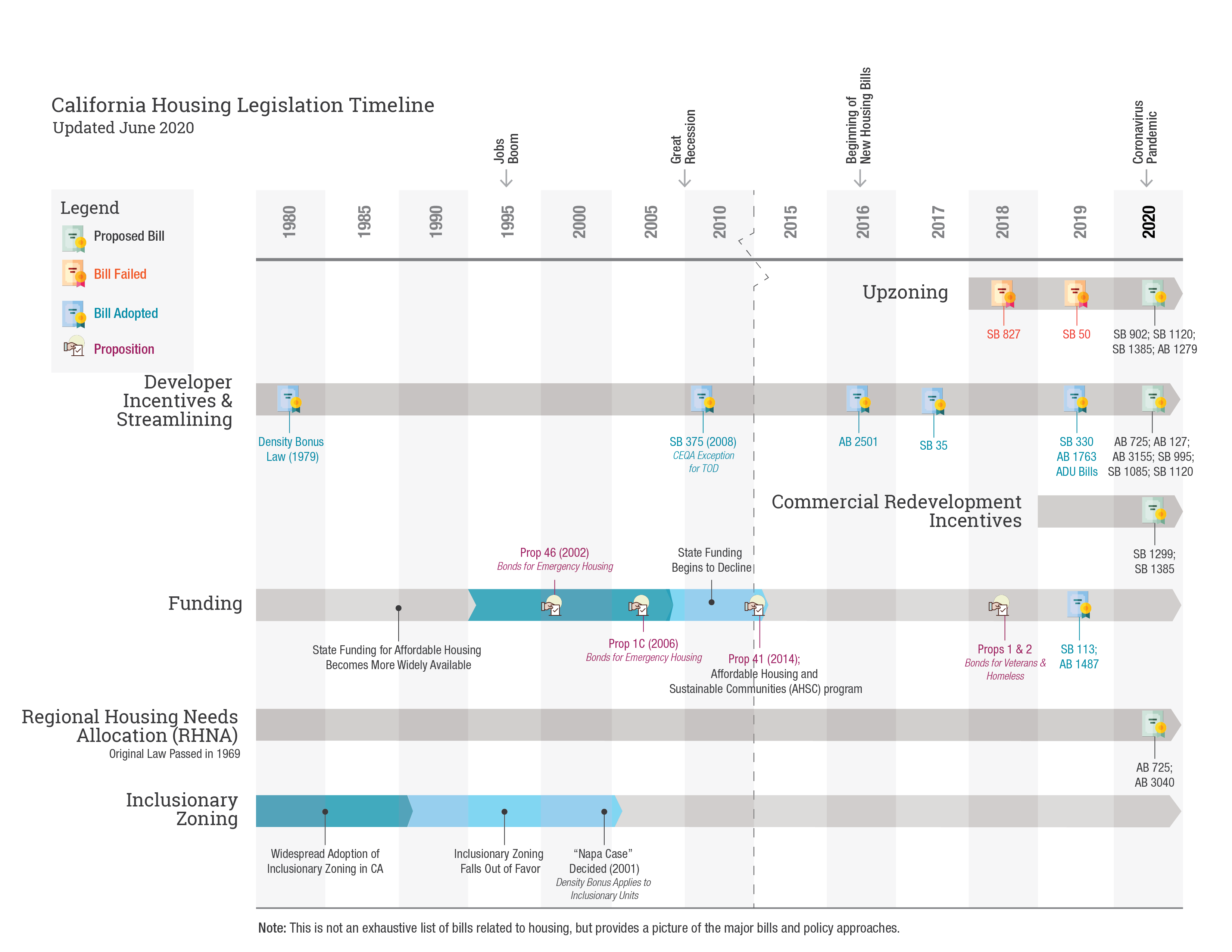

Even during the economic boom that just ended, the state never resumed funding for affordable housing at the same level, despite a doubling of income tax revenue (Embarcadero Institute, 2020). The state collected almost $100 billion dollars in income tax last year, up from just over $40 billion a decade ago. But spending on affordable housing still languished, despite a number of voter-approved propositions that allowed the state government to take on debt for affordable housing (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. State Income Tax Revenue Doubles While Its Spending on Affordable Housing Stagnates

Over the last few years, rather than restoring funding, some state legislators have blamed local zoning and tried to use state-mandated density bonuses to spur affordable housing development. Now adopted bills including SB-330 (2019), AB-1763 (2019), SB-35 (2017), SB-375 (2008) and recent amendments to the Housing Density Bonus Law (originally adopted in 1979), were designed to stimulate affordable housing production through the streamlining of approval processes, the provision of additional density bonuses as incentives, the creation of CEQA exemption, and the supply of a new funding mechanism for sustainable affordable transit-oriented development (TOD).

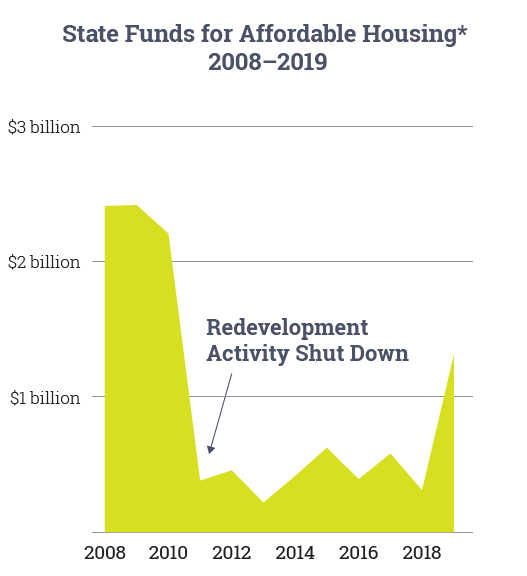

Although it is still too soon to assess the impact of the two bills passed in 2019, it seems clear that prior incentive approaches are not working as the state is building less new affordable housing than it was in the 2000s (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3. New Construction of Affordable Housing

1. More Developer Incentives, Fewer Affordability Requirements

Rather than address the affordable housing crisis head-on by restoring funding, state legislators now seek to extend the affordable housing development incentives to market-rate housing. Many of these bills (AB-1279; AB-3155; SB-1385) offer additional developer incentives (e.g. increased density) while lowering affordability requirements (e.g. agreements to provide affordable housing) already in place in existing law. Overall, this year’s bills offer more incentives to construct housing of any kind (especially duplex units) with less emphasis on the need to provide affordable units. As a result, this could lead to fewer affordable units being constructed as the statewide requirements to receive bonuses may require fewer affordable units.

Streamlining and incentives originally put in place to encourage low-income housing are now on offer for higher income brackets in the current bills (SB-1120, AB-1279, SB-995). These new incentives add further complexity to an already complex system of incentives and have the effect of overriding current law and pitting the production of higher-income housing against lower-income housing – an unfair fight. According to some studies, misaligned incentives (and requirements) is already an issue with some inclusionary zoning ordinances, which the latest bills do not address or attempt to solve (Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley).

In addition, three of these bills (SB-902, SB-995, and SB-1085) provide additional exemptions to CEQA review. The necessity and value in providing these exemptions is unclear but appears to benefit larger market-rate housing projects that would be constructed regardless of these additional exemptions. Further, SB-375 (adopted in 2008) already allows CEQA exemptions for qualified housing projects near major transit.

2. Reliance on Fees-in-Lieu

Perhaps even more damaging to the cause of affordable housing are new in-lieu fees (fees developers can pay instead of building the required affordable housing). The fees suggested in-lieu of building affordable housing are far below the actual cost of building the units, creating an attractive arbitrage for developers of market-rate housing. Fees that are set far below the cost of on-site performance inherently result in little affordable housing (Inclusionary Housing.org).

With an increased reliance of some of these bills (AB-1279 and AB-3155) on fees-in-lieu of providing affordable housing units, it is unclear if funds that are generated will be enough to subsidize other affordable housing projects. Will these fees generate anywhere near the amount of funding to effectively subsidize affordable units in a reasonable timeframe? In many cases, these fees are much smaller than the actual cost of constructing an affordable unit and may actually reduce the number of affordable units that are built if the developer opts to pay a fee.

It is reasonable to assume that the market will take care of market-rate housing. If this is the case, then the state should focus on using tax dollars to help fund state mandated affordable housing and meet RHNA targets. The real affordable housing story is that we lag in production because the state does not choose to fund it (Embarcadero Institute, 2020).

Future bills should consider the variety of funding mechanisms available to developers and local governments and investigate ways to make sure each funding model is sustainable and large enough to fund the affordable housing needed to meet existing state targets and need.

3. Upzoning and Continued Erosion of Local Land Use Authority

Although the proposed bills with an upzoning element (AB-1279; SB-902; SB-1120; SB-1385) are not as heavy-handed as the failed SB-50 and SB-827 (which would have superseded most local zoning controls and allowed higher densities) the proposed bills still represent an override of local zoning codes and the land use element in local general plans.

This year’s set of bills move away from proposing higher densities around major transit stops or in “jobs rich” areas, to instead encourage duplex, triplex, and fourplexes by offering additional streamlined approval incentives or allowing upzoning in existing single-family neighborhoods. Although this may serve middle-income buyers, this approach will not create affordable housing in high-density markets where affordable housing is needed most (e.g. the Bay Area, Los Angeles, and San Diego). According to the most recent Regional Housing Need Assessment permit reports, counties are not having trouble reaching the state’s market-rate housing goals (Embarcadero Institute, 2019).

4. Affected Areas Remain Undetermined

Over and above the market concerns, a number of these bills (including AB-1279 and SB-902) continue to emphasize “objective design standards” in an effort to ensure vaguely written land use regulations (such as subjective design controls) are not used to deny otherwise compliant housing projects. However, many of these same bills use vague or complex criteria to determine areas where local governments should or must allow higher densities, housing types, or offer concessions. Because these criteria are often vague and rely on findings released by the Department of Housing and Community Development after the bill is passed, it is impossible to analyze the neighborhoods and areas that may be impacted by these new requirements.

In addition, municipalities and counties are already required to have a General Plan with chapters on housing and Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA) targets. Local plans are generally informed by knowledge of the sites best suited to affordable housing development. No data suggests that state forays into municipal planning are providing positive results but are burdening local governments with additional development process and compliance requirements.

5. Economic Uncertainty & Changing Housing Markets

Finally, these bills are being considered during an uncertain time, when California and the nation are facing a deep recession and a potentially weakened housing market (CalMatters). The uncertain future economic outlook for state and local governments, not to mention private property owners, developers, and businesses, will undoubtedly impact the residential and commercial real estate market in California.

In the short term, increased unemployment and economic uncertainty could lead to a softening of the housing market, though not necessarily uniform across all areas (CoreLogic Housing Analysis). Early real estate market data points to an increased interest in small cities and rural areas Redfin, 2020). With the shift to remote work, and an uptick in California’s domestic out-migration, real estate insiders are preparing for “a seismic shift towards smaller cities” (Redfin, 2020). Longer term, the economic hangover from the shelter-in-place order could delay and/or reduce construction of new housing. With a potential market disruption upon us, pressing ahead with the ‘old normal’ may place the California State Legislature out of step.

3. Summary Descriptions of Proposed Bills

The following are short descriptions and potential changes for six of the main housing bills currently being considered. A summary table of these bills and others being proposed can be downloaded here.

AB 1279 – Housing Development: High-Opportunity Areas

Assemblymember Bloom | Based on 7/22/2020 Senate Version

This bill introduces “opportunity areas” a term now in use by the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC) to define areas that qualify for low-income tax credits. “Opportunity areas” will potentially align with the CTCAC opportunity maps but notes they will be defined at a later date, after the passage of the bill, by unspecified “academics”. The areas currently defined by CTCAC are posted here: https://belonging.berkeley.edu/tcac-2020-preview

Within high-opportunity areas, residential developments would be a “use by right” (up to 50 units at 40ft max height OR up to 120 units at 55ft max height), upon the request of a developer, if certain affordability requirements are met (varies by number of proposed units).

In addition, housing projects with up to 10 housing units would be a “use by right” if all 10 units were for moderate-income housing (100% of Area Median Income — AMI) OR a developer pays a fee to build market rate units. The fee calculation differs if the housing units are for ownership or rental, but the expected fee amounts may be lower than the amount necessary to construct the equivalent affordable units elsewhere.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Would expand affordable housing development density bonus incentives to more (or larger) areas.

- Appeal process for cities to dispute designated areas (unlike previous bills).

Issues and Considerations:

- Designation criteria is vague and does not use objective standards (e.g. household income thresholds to determine excluded areas). Areas may be substantially similar to those already proposed OR may consist of large portions of many cities.

- High Opportunity Areas would be designated by statewide committee, not local authorities, although input is required from local agencies. Areas designated through top-down process instead of from individual community needs.

- May not provide incentives to develop housing in areas where people who need affordable housing already live as low fees-in-lieu may encourage market rate housing development that can take advantage of bonuses.

Possible Changes:

- Opportunity zones should be clarified up front and should be consistent with areas identified for housing development in the RHNA process. All possibilities of paying in-lieu fees instead of building affordable housing should be set to ensure affordable housing can be built elsewhere.

AB-2345 – Planning and Zoning: Density Bonuses

Assemblymembers Gonzalez and Chiu | Based on 5/22/2020 Assembly Version

Existing law grants density bonuses to developers on a sliding scale allowing them to enlarge a housing project by 20-35% depending on the percentage of affordable housing units in the project. The 35% density bonus is reserved for projects that include either 11% very-low-income units, 20% lower-income units, or 40% moderate-income units.

SB-2345 alters the density bonus scale. Projects that currently qualify for 35% are now eligible for a 50% density bonus. A “density bonus” allows an increase in the total number of units as a reward for having a certain percentage of affordable housing units. On the surface that seems like a good thing, however, the extra housing units are typically market-rate, and that is where the issue lies.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Offers up to six incentives if affordability requirements are met, but the effect on incentivizing more affordable housing is unclear.

Issues and Considerations:

- Under current law, a 100-unit project, where 25% of the units are low-income, would qualify for a 35% density bonus. It would create 110 market-rate units and 25 low-income units. AB-2345 would increase that density bonus from 35% to 50%, which would instead create 125 market-rate units and 25 low-income units – the same number of affordable units but more market-rate housing units.

- The bill effectively incentivizes market-rate, not low-income housing. For every one low-income housing unit, it would create five market-rate housing units (1:5). This ratio sits in stark contrast to the housing need determined by the HCD that claims the state needs to build six affordable housing units for every four market-rate units (6:4).

Possible Changes:

- This bill should not be passed as current law is more supportive of affordable housing.

SB 902 – Housing Development: Density

Senator Wiener | Based on 5/21/2020 Assembly Version

This bill would authorize a local government to pass an ordinance that overrides any existing local restrictions (including those passed by voter initiative) on adopting zoning that allow up to 10 units of residential density per parcel, if the parcel is located in a transit-rich area, a jobs-rich area, or an urban infill site (see Note 2). Areas designated by this ordinance would not be considered a CEQA project, providing an additional incentive/exemption.

This bill evolved out of Senator Weiner’s previous upzoning bills (SB-827 and SB-50), which both had an affordability component. SB-902 does not have an affordability requirement but continues the push to upzone large areas in many cities, including single-family neighborhoods and areas protected by voter approved initiatives. By allowing upzoning of any parcel at any time, it potentially upends existing precedents against spot zoning and introduces a conflict with state law that allows local voter initiatives to have precedence.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Does not have an affordable housing component, but is focused on smaller market-rate units including duplexes and fourplexes.

Issues and Considerations:

- Expands areas that may be upzoned to include may single-family neighborhoods. As with SB-50 and AB-1279, areas will be designated after passage of the bill by the Housing and Community Development Department. This means that the effects of the bill cannot be adequately evaluated in its current form.

- Allows City Councils to override existing ordinances and voter approved initiatives, rendering them irrelevant.

- Although the bill seemingly allows local control over zoning, it erodes longstanding law that allows voters to approve ballot initiatives to protect existing neighborhoods, conservation areas, etc.

- Unclear how new zoning ordinances would be considered and applied. Potentially allows specific developments to be traditional “spot zones” under existing law.

Possible Changes:

- Since the state’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment has set targets of 40% market-rate, 20% moderate and 40% low-income, upzoning should be favored only if developments reflect those percentages. This bill favors market rate over affordable housing, undermining the ability of any city that might adopt this law to reach their state required RHNA affordable housing quotas.

SB 995 – Jobs and Economic Improvement Through Environmental Leadership Act of 2011: housing projects

Senators Atkins, Wiener, Caballero, and Rubio | Based on 7/27/2020 Assembly Version

In 2008, SB-375 introduced a CEQA fast-track for infill affordable housing built near transit. SB-375 is now part of the California Public Resource Code. The law requires a developer to include affordable units within a housing development, to qualify for CEQA fast-tracking: either 20% moderate-income units, 10% low-income units or 5% very-low income units.

SB-995 attempts to reduce the qualifying standard for a CEQA fast-track, lowering the affordable percentage requirement to 15% moderate-income. While a project is still required to be infill, there is no requirement that it be within a certain distance of public transit.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Expands areas where affordable units would qualify for CEQA exemptions and potentially benefit from a master Environmental Impact Report (EIR).

Issues and Considerations:

- SB-995 lowers the percentage of affordable units a developer must include to qualify for CEQA fast-track — this, even as the state comes up short on affordable housing. Lowering the state’s requirement for moderate-income units to 15% is at odds with state affordable housing goals set by the Department of Housing and Community Development at 60% (40% low and very low Income housing units + 20% moderate income units). SB-995 further erodes the ability of cities to reach their affordable housing targets, yet without a rationale. If legislators believe incentives are the path to building sustainable affordable housing, they should align these incentives with the targets they have set for cities.

- This bill creates conflict between HCD’s established Regional Housing Needs Allocations (RNHA) targets as well as California’s Public Resource Code.

Possible Changes:

- The bill is unnecessary given existing law.

SB 1120 – Subdivisions: Tentative Maps

Senators Atkins, Caballero, and Wiener | Based on 7/27/2020 Assembly Version

This bill would require a proposed housing development containing 2 residential units or an “urban lot split” to be considered ministerially (without discretionary review or hearing) in zones where allowable uses are currently limited to single-family residential development. This effectively allows duplex development to be a “use by right” around the state, regardless of local zoning or general plan guidelines. The bill also allows for a CEQA exemption and reduced/no parking requirements for developments near public transit.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Does not support affordable projects. However, projects are not eligible if the development would involve demolition of existing units inhabited by persons and families of moderate, low, or very low income.

Issues and Considerations:

- Potentially upzones single-family areas in many communities with single-family zoning to allow duplexes (and potentially fourplexes). Overrides local zoning authority.

- There is no need to incentivize market-rate housing with a reduced parking requirement or streamlined approval process. Reduced parking requirements should be exclusive to low-income housing developments. Parking for market-rate housing should follow local zoning rules.

- Lot splits allowed by right. Might interact with minimum lot sizes regulated by local governments (i.e., encourage more lot splits).

Possible Changes:

- Need to clarify whether a developer may use the bill to split a lot and then develop 2 units on each new parcel (creating 4 new units) or if the urban lot split can only be used to support developments with 2 units.

SB 1299 – Rezoning of Idle Retail Sites

Senator Portantino | Based on 6/18/2020 Senate Version

This bill would allow local governments to apply for state grants to help rezone idle sites used for a big box retailer or a commercial shopping center to instead allow the development of workforce housing (housing for households with income greater than or equal to 80 percent of the area median income, but no more than 120 percent of the area median income). This bill creates an incentive to convert idle big-box retail to moderate income work-force housing projects.

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Provides incentive to local governments to redevelopment idle retail sites. Could spur larger redevelopment projects that create more housing of sites that might otherwise remain idle.

- Workforce housing requirement that targets low income to moderate income households.

- This is the only bill that addresses funding challenges for cities. It creates an innovative economic incentive for cities to convert big-box to housing. The carrot versus the stick approach.

Issues and Considerations:

- Affordable housing targets could be broadened to include households with incomes lower than 80% of the area median income.

- Program may not be widely used if funds are not enough to incentivize local governments to rezone.

- Rezoning may start the conversation, but will it resolve the issue? Projects still need a developer to take over site and develop.

Possible Changes:

- None.

SB 1385 – Housing: Commercial Zones

Senators Caballero and Rubio | Based on 6/18/2020 Senate Version

Establishes a housing development project as an authorized use on a neighborhood lot zoned for office or retail commercial use, making residential uses allowable on existing office or retail commercial zoning locations. Proposed housing development projects would have to comply with all of the following:

- The density for the housing development must meet or exceed the applicable density deemed appropriate to accommodate housing for lower income households under housing element law.

- The housing development is subject to local zoning, parking, design, and other ordinances, and must comply with any design review or other procedural requirements imposed by the local government.

- The commercial and office site needs to have had 50% of the square footage vacant for three years or more to be eligible.

If housing projects meet these requirements, they may consist of entirely residential units or a mix of commercial retail, office, or residential uses. Projects would be for SB-35’s streamlined ministerial approval process and would allow a project to request that a local agency establish a Mello-Roos Community Facilities District (for financing of site infrastructure and improvements).

Potential Affordable Housing Benefits:

- Incentivizes redevelopment of retail and office sites. May be beneficial with many vacant commercial sites due to Coronavirus and the “retail apocalypse”.

- Unknown effect on affordable housing development, as proposed developments would not have specific affordability requirements beyond local zoning requirements (such as inclusionary zoning).

Issues and Considerations:

- Does not have an affordable housing incentive or requirement.

- Unclear how residential zoning standards would be applied to commercial and office zoned areas.

Possible Changes:

- None

Notes:

Note 1: Definition of High Opportunity Areas (AB 1279):

(A) The department [Housing and Community Development] shall consider any area designated as “highest resource” or “high resource” on the most recent Opportunity Maps adopted by the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee as a potential high-opportunity area.

(B) The department shall not designate a potential high-opportunity area as a high-opportunity area if either of the following conditions apply:

(i) The area is at risk of displacement of lower income households and households of color, or has seen significant displacement of lower income households and households of color within the 10 years preceding the designation of high-opportunity areas pursuant to this subdivision.

(ii) Low wage workers in the potential high-opportunity area do not have significantly longer commutes to work than other low wage workers within the region.

(C) In determining potential high-opportunity areas to be excluded from the designation of high-opportunity areas pursuant to this subdivision, the department shall seek input from community-based organizations with experience working with low-income communities and communities of color.

(D) The department shall update its designations of high-opportunity areas pursuant to this subdivision within six months of the adoption of new Opportunity Maps by the California Tax Credit Allocation Committee.

Note 2: “Urban infill site” means a site that satisfies the following:

(A) A site that is a legal parcel or parcels located in a city if, and only if, the city boundaries include some portion of either an urbanized area or urban cluster, as designated by the United States Census Bureau, or, for unincorporated areas, a legal parcel or parcels wholly within the boundaries of an urbanized area or urban cluster, as designated by the United States Census Bureau.

(B) A site in which at least 75 percent of the perimeter of the site adjoins parcels that are developed with urban uses. For the purposes of this section, parcels that are only separated by a street or highway shall be considered to be adjoined.

(C) A site that is zoned for residential use or residential mixed-use development, or has a general plan designation that allows residential use or a mix of residential and nonresidential uses, with at least two-thirds of the square footage of the development designated for residential use.

Note 3: Income Definitions:

Income definitions for affordable housing in California are defined in The Health and Safety Code, Division 31, Chapter 2. Definitions. [50050 – 50106]